2019 turned out to be an excellent reading year. I would not hesitate to recommend any of the following books to readers who are fine with weird, funny, and often miserably sad stories.

You can watch me in a video talking about this list here: https://youtu.be/XEiGPE3efCg

The Backlist (books that were published before 2019):

You Think It, I’ll Say it, Curtis Sittenfeld

Short stories about middle-aged people, not necessarily nice or pleasant, dealing with relationships. Sittenfeld’s style is always charming; she’s funny but is not easy on her characters. They’re flawed and often vindictive and selfish. But they’re relatable, too. The stories don’t shy away from the politics of the time, which is essential. Ignoring our calamities would make these stories less powerful.

The Mountain Lion, Jean Stafford

A slim novel that bounces between the two main characters, a brother and sister who are bonded and seem throughout to be united in their contempt for other people, especially their mother and older sisters. The portrait of these characters is not to elicit sympathy, but to draw on the deep well of loneliness and a dawning realization of what growing up can mean. Most of the book takes place in the Colorado mountains during the 1930s; the children take dirty trains to visit their uncle there and are surrounded by people far removed from their mother’s pristine, prissy sitting room and the fawning next-door minister who comments on their behavior incessantly. Stafford builds a world that contains the brutal practices of hunting and farming; peril lurks around every corner, but nothing in the outside world can rival the peril of the children’s private thoughts. That’s as much as I want to say about the book without giving up its mysteries. If you want to read it, go in as blindly as possible.

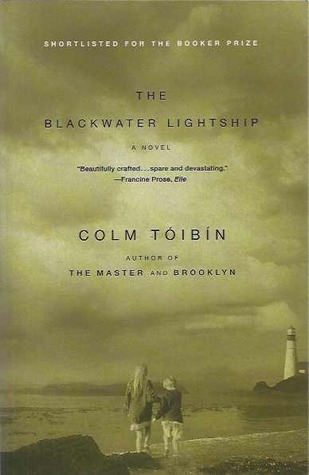

The Blackwater Lightship, Colm Toibin

A novel about a 1990s Irish family, long fallen out, who must come together when one of the siblings is near the end of his life from AIDS. The main character, Helen, must try to put aside deep pain and anger to be with her mother, brother, and grandmother, and in the week they co-habitate, confront the past. The dialog is raw and direct, and the setting, a house on a cliff overlooking the sea, complements the tone.

Mad Boy: An Account of Henry Phipps in the War of 1812, Nick Arvin

A coming of age tale of a boy who’s life is upended when his mother dies and the British are approaching Alexandria in the War of 1812. This book is packed with action, memorable characters, and a sly, sometimes unhinged humor. There’s a core of loneliness that underlies everything, but that’s true of all the best novels.

Accordion Crimes, Annie Proulx

The frame of this novel is the history of a single accordion, from its manufacture in Italy to the late twentieth century. But the rollicking heart of this story is of people and their cultures, how this one simple accordion encompasses so many styles of music, all of which are an integral part of the immigrant experience. America is here in messy, hot-hearted, bigoted, hateful and loving expressions. Life and death, disfigurement, addiction, and the private agonies of lost loves are here in Proulx’s frenetic, unsparing style.

Severence, Ling Ma

This is a take on the zombie apocalypse, not generally one of my go-to types of novels, but it branches from there to be a metaphor of the way we’re living now, without a monster (i.e., the monster is us.) The story is told from the perspective of one young woman who before the event worked in bible publishing. When most people die, she goes off trying to find other people.The story is full of lonely people who were untethered from others even before the virus takes over.

The Known World, Edward P. Jones

On the surface, this novel is the story of a short period of time after black slave owner Henry Townsend has died. He was thirty-one, married to a free woman named Caldonia, and they owned thirty-three slaves at the time of his death. Henry was born a slave, but his parents worked hard to buy their own freedom and then Henry’s freedom several years later. This is the barest plot summary possible, because in actuality, the novel contains multitudes.

The Vagrants, Yiyun Li

Set in China in the late 1970s, this novel is about a small province that is shaken by the politics of Beijing. One of the women in town who had been a leader of the Cultural Revolution and all its horrors repents and rebels against the government. She is sentenced to be executed for crimes against the state, and the reverberations of that act are what the novel is about. Her parents are key characters, yet there are many others here and their stories are linked by fate. Such a great work. It would be a good book club discussion novel.

Do Not Say We Have Nothing, Madeleine Thien

Describing this intricate novel is hard. It’s family saga, political history, and culture woven into fiction. When politics are weaponized to tear a nation apart and break people down so that their deepest thoughts and desires must lay hidden in order to adhere to arbitrary and dehumanizing rules of order, the individual is lost and families are broken. That’s what happens to this novel’s characters in the wake of the Cultural Revolution and then the days of the Tienanmen Square massacre. This was a hard novel to stick with, not because the writing isn’t beautiful and effective, but because the characters’ miseries are agonizing to witness. Yet I’m still thinking about it.

When Will There Be Good News, Kate Atkinson

This is my favorite of the Jackson Brodie series, and it features a remarkable teenage protagonist who ends up helping Jackson in one of his darkest moments. Funny, weird, and scary. So good.

Books Published in 2019

Ducks, Newburyport, Lucy Ellmann

What could have been a gimmicky novel turns out to be a prolonged cry against the modern world and its cruelties, as well as a heartfelt story about a woman’s grief. Yes, the main part of the novel is one sentence, but you quit thinking about that a couple of hundred pages in if you’ve made it that far. The main character is in an anxiety loop she can’t seem to break, and we see her brain jump from memory to worry about her kids to her deep love of her husband to her existential angst about how many chickens we’re eating every day. The effort it must have taken to write and edit this work, and the chance the publisher took to put it out in the world only to almost lose the business over the onerous requirements of being on the Booker Prize shortlist, and the cumulative effect of the work on your own brain as you spend so many hours with this person, make it all worth it. Women’s stories matter.

The Topeka School, Ben Lerner

A challenging novel about a family in Topeka, Kansas, in the last quarter of twentieth century. The parents work for a renowned psychology training institute/mental health hospital called The Foundation and they have a smart and often angry son named Adam. The novel is divided into chapters between Adam, Jane (his mother), and Jonathan (the father), where the main story unspools. There is also an account at the ends of these chapters of a fourth, an outcast named Darren, who bears most of the torment his classmates pile on him.

While this is an insular family saga, it’s also a chilling social commentary, a deep exploration of the limits of language to express existential discord and looming systems collapse. It’s a targeted indictment of politics, systems, and child rearing practices from the 1990s to the current day. The Topkea School manages weave together distinct voices, science, sociology, economic systems, misogyny, and dread. We end up caring deeply for the characters but hurting for our world.

The Dutch House, Ann Patchett

At its core, this is a novel about the intense bond between siblings in the aftermath of their family’s disintegration. Set in the late 1960s and beyond in Pennsylvania and New York, the story is told by the brother, Danny, and jumps around in time from his early childhood till late-middle age. He and his older sister, Maeve, have each other to work through their deep longing for lost family, symbolized by a house their father bought as an impetuous grand gesture.

Fleishman is in Trouble, Taffy Brodesser-Akner

A raunchy, funny divorce novel on the surface that turns out to be something completely different in the end.

Trust Exercise, Susan Choi

This novel asks readers to abandon preconceived ideas about what a novel should be and allow three characters to share their own specific experiences that (tangentially) center on a failed high school romance. Go into it knowing as little as possible and see what you think.

I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution, Emily Nussbaum

Even if you’ve already read Nussbaum’s New Yorker columns faithfully, the new essay, Confessions of a Human Shield, is worth the price of the book. In it, Nussbaum examines her own journey from liking and defending the work of difficult men to understanding how they fit into our current cultural morass. Particularly blistering is her discussion of the fate of Louis CK. It’s an essay of and for our time. The rest of the essays are reviews of television shows like The Sopranos and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. What I like about Nussbaum is her lack of a need to please the reader. These are her opinions and she doesn’t care if you don’t agree.

Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations, Mira Jacob

A graphic novel about race and identity in Trump’s America, especially if family members can’t see how much harm and hate (which were always here) have emerged to rip apart our communities. I love the book’s drawing style and confessional story.

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland; Patrick Radden Keef

This book takes on the difficult task of bringing the politics, sectarianism, will, and folly of the Troubles of Northern Ireland to the page. The muddled history of the times are brought to life with portraits of the people who lived in a climate of secrecy and death sentences for those who betrayed the cause. It is tense and frightening, and shows that domestic terrorism mixed with the harsh brutality of the State caused suffering and needless deaths. How do we reckon with the past while at the same time try to forge a future that sets aside old hatreds? It might be the crux of human existence, and there are lessons within this struggle to apply to the new and the ancient.